The Absurdity of the Everyday

by Martin McGuigan

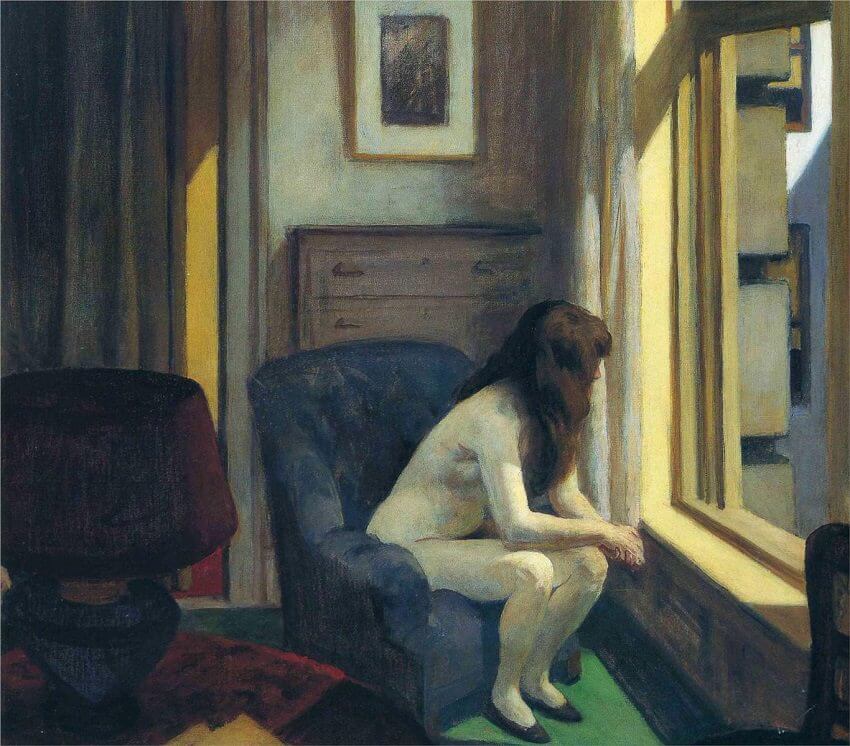

There’s a painting by the American artist Edward Hopper called ‘Eleven AM’. It shows a woman, naked, perched in an almost indifferent posture on a blue chair. The room is densely furnished, but she is alone.

She stares out of a window next to her, toward a view we cannot see. Likewise, her eyes are hidden – but if we could see them, they would be indifferent.

In this scene, we are not seeing anything extraordinary. In fact, quite the opposite – something very ordinary: the feeling of being with ourselves by ourselves.

In many of his paintings, Hopper channels that very well.

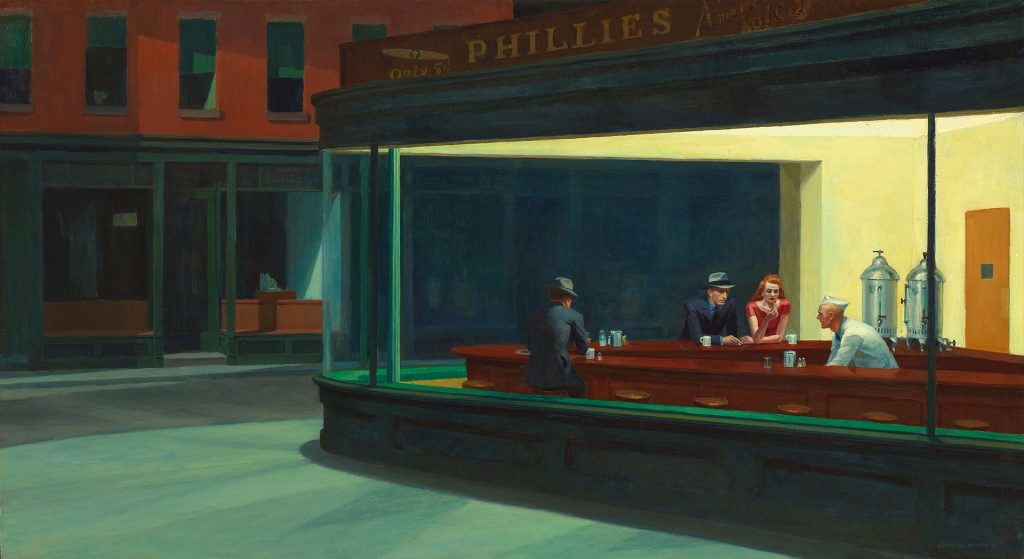

Perhaps the most famous example of this is ‘Nighthawks’, which captures this feeling just as effectively as the lonesome woman.

Like ‘Eleven AM’, ‘Nighthawks’ shows something very ordinary and all too common: solitude.

Within this late-night New York diner, there are a few individuals – a server in white, and a man only visible from behind, both with a detached expression and posture. Most notably, there’s a man and a woman. Spouses?

Possibly – but if so, only in name.

The woman stares at a green object within her fingers with a detached gaze. The man looks toward the server with anticipation, perhaps to request something – but that too is indifferent.

They all are close in proximity, but distant individually. The diner itself is a beacon of light in an otherwise dark exterior, but it is a façade, and no remedy for the hollowness these people feel.

They are living encapsulations of that feeling once more — to be with ourselves by ourselves.

In both paintings, no one – except perhaps the perched woman – is exactly alone. They are either surrounded by furniture or their fellow man, but nothing can seem to break through and fill the yearning hollowness they feel.

What is so disturbing about this is that it’s all too common, and all too familiar to us.

To be surrounded, but alone.

To be there, but not here.

This poses a question: what does it mean to be alone – not just socially or physically, but inwardly?

It’s a question we may ponder as we lie in our beds at the beginning of our days, and for many of us it may be the very justification for why we get up – to avoid it.

Why is this?

I believe the answer is rooted in the inherent absurdity of everyday life – to get up, work, and live without thinking, without questioning, and in illusions.

The idea itself is akin to Albert Camus’ notion that we live in an indifferent and inherently absurd universe – that we desire answers from it, but only converse with silhouettes.

Perhaps absurdity then is not, for us, a crisis, but simply a condition – an outline, a fluorescent light, a silent hum of late morning.

What now? What do we do with this knowledge of absurdity?

Rebel.

But not in revolution – in opposition.

For rebellion is not in fighting absurdity; it is living in spite of it.

It is to sit with it, and to learn to see it for what it is: absurd.

Not to despair or embrace it, but to realise we are Sisyphus, forced to push the stone uphill.

We must push our responsibility of seeking and creating meaning up our own hills.

That is our duty – not to embrace, but to oppose. To push.

We must be happy, as we must imagine Sisyphus to be.

For all he is, is a reflection, and a projection of ourselves.

We must, in this pursuit, be with ourselves by ourselves.

Latest Articles

- The Neglected Value of BreastfeedingOn the benefits of breastfeeding

- Architecture Without a FutureOn architectural historicism

- The Absurdity of the EverydayOn seeking and creating meaning

- Bridging Science and SocietyOn interdisciplinary collaboration

- Renewable Baseload PowerOn the future of energy

- AI and the Battle for CommunicationOn control of communication

- Operating in a Bitcoin WorldOn the new monetary order

- Beyond Political NostalgiaOn hope as a political force

- The New Age of CaesarsOn the end of liberal democracy

- Social Media: Five Stages of GriefOn reclaiming our attention

About the author

Martin McGuigan is an independent and self-taught thinker. He explores ideas and tests assumptions with understanding and rigour, driven by a desire to deepen his understanding and unlock his potential.

Updates

Sign up to the CATALYST Updates Substack to receive the monthly schedule for new articles, news on the physical print-run of CATALYST’s inaugural issue, and details on the upcoming CATALYST Conference.